Make a Copyright U-Turn

Make a Copyright U-Turn and Other Audacious Statements about Copyright and Educational Fair Use

Pennsylvania School Librarians Association journal, Learning and Media

Doug Johnson

doug0077@gmail.com

September 2008

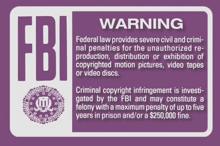

First image above is the standared FBI warning preceding commercial videos. Image below is from Eric Faden’s “A Fair(y) Use Tale” at Media Education Foundation <http://www.mediaed.org/>

Few subjects engender more disagreement and confusion than intellectual property, copyright, and digital rights management. These are areas where I feel less and less certainty that as a professional I have a firm understanding and philosophy.

I am not alone. The 2007 document “The Cost of Copyright Confusion for Media Literacy” published by American University’s Center for Social Media coins a new term: hyper-comply. It means that some educators over-comply with copyright law, and even forego using legitimate teaching tools and techniques for fear of violating copyright. Along with hyper-compliance, the study found that studied ignorance and clandestine transgression lead to schools where teachers use less effective teaching techniques, teach and transmit erroneous copyright information, fail to share innovative instructional approaches, and do not take advantage of new digital platforms.

How we teach copyright and other intellectual property issues is overdue for an overhaul in our schools. The library media specialist’s role as “copyright cop” needs serious revision especially. The mindset that “if we don’t know for sure that it is perfectly legal, don’t do it” no longer fits the needs of either students or their teachers. Below are four changes our profession must seriously consider.

1. Change the focus of copyright instruction from what is forbidden to what is permitted.

As information professionals, we have as great an obligation to see that staff and students get as full access and use of copyrighted materials as possible, as we do in helping make sure they respect copyright laws.

Our instructional efforts need to include teaching users that the use of copyrighted material in research, if properly cited, and if it supplements rather than supplants the researcher’s product is perfectly legal. The question we should be asking is not “What percent of another’s work did you use?” but “What percent of your product is of your own making?”

We also need to teach the concepts and tests of Fair Use. Both staff and students should be able to name and explain the factors surrounding Fair Use, “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research…” Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 10

We need to be teaching that a copyrighted work’s use is considered Fair Use if it is of a “transformative” nature. In Recut, Reframe, Recyle, the authors define these uses of copyrighted works in online videos as “transformative” and meeting Fair Use guidelines:

- · Parody and satire

- · Negative or critical commentary

- · Positive commentary

- · Quoting to trigger discussion

- · Illustration or example

- · Incidental use

- · Personal reportage or diaries

- · Archiving of vulnerable or revealing materials

- · Pastiche or collage

All teachers need to understand every special right given to them as educators. Teachers can show personal copies of copyrighted videos to a class; off-air broadcasts can be re-shown to classes; and photocopies of copyrighted news and magazine article can be given to students. (Some restrictions apply, but these are all legal uses.) The Fair Use Guidelines For Educational Multimedia clearly state that educators may create educational multimedia projects containing original and copyrighted materials and may use those projects for face-to-face student instruction, directed student self-study, real-time remote instruction, review, or directed self-study for students enrolled in curriculum-based courses, and presentation at peer workshops and conferences. Educators also need to know that students can use copyrighted materials for educational projects in the course for which they were created and in portfolios as examples of their academic work for job and graduate school interviews.

Educators need to know the outer limits, not just the safe harbors of the use of copyrighted materials – and allow their students to explore those outer limits as well.

2. When there is doubt, err on the side of the user.

A Singapore educator once shared with me that his countrymen tend to suffer from NUTS - the No U-Turn Syndrome and Americans do not. When no signs are posted at an intersection, Singapore drivers assume U-turns are illegal; US drivers assume they are legal. He felt the “assume it is OK” attitude gives our country a competitive edge. It really is better to ask forgiveness than permission.

An educator’s automatic assumption should be that, unless it is specifically forbidden and legally established in case law, the use of copyrighted materials should be allowed.

A high profile example of moving to a forgiveness-based approach comes from Google’s Scan the Book project. In its effort to transform all the world’s books into a digital, searchable format, Google found that 15% of the world’s cataloged books are in the public domain and 10% are actively in print, but 75% of the world’s books are “in the dark” – neither being made available by publishers nor in the public domain. Since few publishers have shown willingness to investigate the actual ownership on these materials, the Google Scan the Book project decided to scan first and then remove the digital copies if requested.

Yes, current copyright law says that everything written in the Unites States is automatically copyrighted. Unfortunately, the will of the owner of the work is always assumed to be that she/he has exclusive rights. With the advent of Creative Commons, an alternative means of describing a creator’s level of control over a work, “exclusive rights” can or should no longer simply be assumed.

When copyright or use warnings are implicitly stated, teachers often disregard uses that fall under Fair Use provision. Most books contain the following standard warning:

“All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.”

Yet as a researcher and teacher, one has the right to do all the expressly forbidden things listed in the warning provided Fair Use guidelines are followed. The two motion picture warnings that begin this article graphically make the same point.

Content creators or providers can impose any sort of restriction they wish without it ever needing to be vetted by a court of law. YouTube’s Terms of Use read in part “You agree not to access … YouTube Content through any technology or means other than the video playback pages of the Website itself, the YouTube Embeddable Player, or other explicitly authorized means YouTube may designate. To my knowledge, there is no U.S. court case to determine whether YouTube has the right to make and enforce such a condition. If I place a “Terms of Use” on a blog that the reader must be drinking gin and wearing a pink bathrobe to read it legally, could I take my readers to court?

Until something is proven illegal, assume it is legal.

Schools and other institutions may place restrictions on the use of copyrighted information that go beyond legal requirements. My own district’s board policy on copyright states: “All of the four conditions [of the Fair Use Doctrine] must be totally met to qualify a work for use or duplication under this clause.” The law itself only reads that these are “factors to consider.”

Finally, consider that there is an inherent bias toward copyright owners when copyright “experts” offer advice about particular situations. A lawyer, a book author or columnist who answers questions on copyright issues may be held liable for the advice they give and usually err on the side of the party most likely to be litigious. As one of my college-era t-shirts read, “Question authority!”

Other places to look for “expertise” that have a more user-centric bias include:

- · Center for Social Media at American University

- · Chilling Effects Clearing House

- · Creative Commons

- · Media Education Foundation

- · Public Knowledge public interest group

- · Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society “Fair Use Project”

Place the onus of proof of wrong doing on the provider, not the proof of Fair Use by the user. Assume the U-turn is legal!

3. Be prepared to answer questions when the law seems to make little sense, when a law is inconsequential, when a law is widely ignored, or when breaking the law may serve a higher moral purpose.

A few years ago, I found that my son had downloaded an illegal copy of one of the Lord of the Rings movies. I asked if he felt bad about depriving Peter Jackson, one of his heroes, of his payment for making the film. His reply was, “Dad, I paid to see the movie twice and I will buy the DVD when it comes out in a regular version and when it comes out in a director’s cut version. I think I am paying Peter Jackson for his creative works. What harm does this digital version cause?”

Simple control over a person’s intellectual property, even if there are no financial considerations, is a concept many find difficult to both explain and defend. And this is just a single example of laws that seem to be dated, overly restrictive or just nonsensical.

As a result, there are intellectual property laws that are so routinely ignored that they have become meaningless - and enforcing them makes the librarian appear to be a martinet. Common violation of copyright that are so routinely ignored as to be meaningless include showing movies in class for entertainment or reward without a public performance license, playing a commercial radio station that plays popular music in a public venue, using copyrighted or trademarked items on school bulletin boards or in locally-produced study materials, converting 16mm films or videotapes that are not available for purchase into DVD, and making copies of materials for archival purposes.

Making copies of copyrighted materials of online resources that can be read online without cost for classes, downloading digital videos, such as those from YouTube, onto a local hard drive, and converting analog materials (text, pictures, video, audio) to digital formats to be used with interactive whiteboard or slide show software for whole group instruction is regularly done by teachers. These uses have either no or minimal impact on a copyright holder’s profits. Overly strict enforcements of the letter of copyright laws will lead to creating scofflaws of not just students, but teachers, and make all copyright restrictions suspect.

It is interesting to note that, according to Temple University’s Media Education Lab, “There’s never been a lawsuit involving a media company and an educator over the rights to use media as part of the educational process.” Which again calls into question the seriousness of the “crime.” Do we turn a blind eye when we see students or staff committing obvious thefts of intellectual property? No, but neither do we need to over-react.

We also must acknowledge that there is a growing movement that believes current intellectual property law, especially copyright, works against the greater good of society. “Free culturists” argue that everyone in a society benefits when creative work is placed in the common domain and everyone is allowed to use and build upon it, and that current copyright laws give the owner too much control and for too long a time. Building on the free and open source software movements, this cult at its most extreme insists that “intellectual property” is a meaningless term.

However, Lawrence Lessig, often seen as the movement’s founding father, writes in his book Free Culture:

A free culture, like a free market, is filled with property. It is filled with the rules of property and contract that get enforced by the state. But just as a free market is perverted if its property becomes feudal, so too can a free culture be queered by extremism in the property rights that define it.

Hobbs, Jaszi, and Aufderheide wisely write: “Applying fair use reasoning is about reaching a level of comfort, not memorizing a specific set of rules.” This statement applies to all issues involving copyright and intellectual property.

4. Teach copyright from the point of view of the producer, as well as the consumer.

The library media specialist’s role is to help each teacher and student establish an informed, personal “level of comfort” in using other’s intellectual property.

Few of us are comfortable at either extreme of copyright enforcement – playing the copyright bully or advocating total disregard of the rules governing intellectual property. Complicating the issue is that each of us is likely to arrive at his/her own personal level of fair use comfort, judgment of seriousness of possible use, and perspective of the morality of intellectual property use both personally and professionally.

And that’s OK. My long-standing philosophy is that education is about teaching others to think rather than to believe. We need to help individual students arrive at personal comfort levels when using protected creative works.

Library media specialists can assume some practical stances toward copyright instruction and enforcement. They must insist that the enforcement of all laws and policies falls on administrators, not teachers or librarians, and rebrand themselves “copyright counselor.” And do what good counselors have always done – help others reach good decisions about their actions. LMS’s should rat out fellow teachers only under a very narrow set of circumstances. LMS’s need not commit any acts they personally deem illegal. In in-services and communications, the LMS should emphasize what can, not what can’t be done with intellectual property.

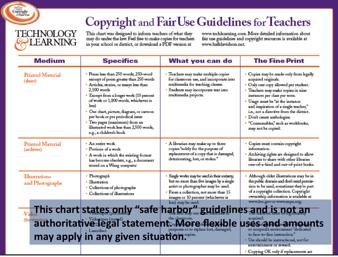

The LMS should modify any signs about Fair Use with be a caveat. The popular chart like the one produced by Hall Davidson should be amended thus:

<http://www.techlearning.com/techlearning/pdf/db_area/archives/TL/2002/10/copyright_chart.pdf>

We can certainly get a student to bubble in the “right” answer on a test about copyright, we can refuse to accept student work that may include copyrighted media, and can say, “think hard about your actions, young woman.” But I doubt any of those actions will stop the illegal downloading of materials once the child is out of sight.

Studies do suggest that teens are not a-moral, but uniformed. From a KRC study conducted for Microsoft:

The more teenagers know about laws against illegal downloading, the more they will come to think it should be a punishable offense. Likewise, teenagers unaware of the rules are more tolerant of illegal activities. Among teenagers who said they were familiar with the laws, more than eight in ten (82%) said illegal downloaders should be punished. In contrast, slightly more than half (57%) of those unfamiliar with the laws said violators should be punished.

We must allow the fair use of copyrighted material in student work, but expect students to be able to articulate why they believe it constitutes fair use. Only when students begin to think about copyright and other intellectual property guidelines from the point of view of the producer as well as the consumer, can they form mature attitudes and act in responsible ways when questions about these issues arise. And as an increasing number of students become “content creators,” this should be an easier concept to help them grasp.

Among the most serious misperceptions about copyright holders is that only big, faceless companies are impacted by the theft. A popular view is that it acceptable to steal from big companies but not from the small fry. Too often adults as well as students forget that many large companies are made up of small stockholders and employees also trying to make a buck. Publishing companies represent the interests of individual artists, writers and musicians - whose ranks students themselves may one day join.

Students should be required to assign a Creative Commons designation to each piece of original work they produce – especially those items they will be publishing online or in print. By thinking about how one wants his/her own work treated, one is forced to consider the rights and wishes of other creators as well. Counseling teachers to use a Creative Commons designation on their work would be a good thing as well.

Increasingly I am looking at the moral issues involved in intellectual property issues. Many states once had segregation laws that required African-Americans to sit at the back of the bus. A brave woman named Rosa Parks defied the law and made history. Are our current copyright laws requiring our students and teachers to sit at the back of the intellectual property bus? How do we respond if a student’s or teacher’s actions seem legally suspect but morally correct? Do librarians and educators have the courage to be the Rosa Parks of the information age?

Resources:

Also at https://dougjohnson.wikispaces.com/NUTS

Aufderheide, Pat, Renee Hobbs and Peter Jaszi “The Cost of Copyright Confusion for Media Literacy.” Center for Social Media <http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/files/pdf/Final_CSM_copyright_report.pdf>

Aufderheide, Pat and Peter Jaszi “Recut, Reframe, Recycle: Quoting Copyrighted Material in User-Generated Video” Center for Social Media <http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/resources/publications/recut_reframe_recycle>

Chilling Effects Clearing House <http://www.chillingeffects.org/>

Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/>

Faden, Eric “A Fairy(y) Use Tale” Media Education Foundation <http://www.mediaed.org/> Available on YouTube at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJn_jC4FNDo>

“Fair Use Project” Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society <http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/node/3136>

Hobbs, Renee, Peter Jaszi and Patricia Aufderheide “Ten Common Misunderstandings about Fair Use” Temple University Media Education Lab <http://mediaeducationlab.com/index.php?page=274>

Hobbs, Renee “Fair Use and the Educational Guidelines: FAQ” Temple University Media Education Lab

<http://www.mediaeducationlab.com/index.php?page=275>

“IP and Free Speech” Electronic Freedom Foundation <http://www.eff.org/issues/ip-and-free-speech>

Lessig, Lawrence. Free Culture. New York: Penguin, 2004.

Kelly, Kevin “Scan This Book,” New York Times, May 14, 2006

<http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/14/magazine/14publishing.html?_r=1&oref=slogin>

Mankato Public Schools’ Guide to Cheating and Plagiarism

<http://www.isd77.org/school305/FCK/File/cheat77.pdf>

Public Knowledge <http://www.publicknowledge.org/>

Stallman, Richard. “The Right to Read.” GNU Operating System <http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/right-to-read.html>

Stallman, Richard M. “Did You Say “Intellectual Property”? It’s a Seductive Mirage.” Free Software Foundation <http://www.fsf.org/licensing/essays/not-ipr.xhtml>

Starr, Linda. “Applying Fair Use to New Technologies Part 4” Education World <http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr280d.shtml>

Topline Results of Microsoft Survey of Teen Attitudes on Illegal Downloading <http://www.microsoft.com/presspass/download/press/2008/02-13KRCStudy.pdf>

Teen Content Creators, Pew Internet & American Life Project <http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Teens_Social_Media_Final.pdf>