Using Planning and Reporting to Build Program Support

The Book Report, May 1992

Professional training teaches one a great deal about the “middle” of one’s job responsibilities. Entire classes in library media education are often devoted to instructional design, selection, A-V production, cataloging, materials for children and young adults, and equipment utilization. And rightfully so, since the competent execution of these duties is how we spend the bulk of our on the job time, working with students and staff to increase learning opportunities.Are you paid at the same rate as the teachers?

Must be nice not having to fill out report cards!

Why can’t you cover teacher prep time? You don’t have anything else to do.

Due to budget cuts, we’re reducing staff. I’m afraid I have some bad news for you.

Yet statements like the ones above are unfortunately too common. And more often than not, the speakers are commenting from ignorance, not knowledge. Few educators outside our own profession really seem to know what we should do, what we can do, and what we actually do. I believe it is because library/media specialists tend to neglect the “ends” of the job: planning and reporting. A formal, systematic procedure for media program planning and reporting can effectively increase staff and administrative support, and should be given a very high priority among the myriad of building level media professional’s tasks.

Seneca wrote, “Our plans miscarry because they have no aim. When a person does not know what harbor he is making for, no wind is the right wind.” I have found that writing a simple planning document which is modified and approved by my building principal and library/media advisory committee gives me direction throughout the year.

I write the planning document in the spring for the following year. The document first describes how the plan is to be used and restates the school district’s library-media program mission statement and district-wide media goals. Building program goals are then divided into seven broad categories:

- Student and faculty research/technology competencies

- The reading program

- Collection development

- Staffing and the physical plant

- Interlibrary cooperation

- Public relations

- Professional development

These are categories which fit my goals; other professionals will have divisions which better suit their own programs.

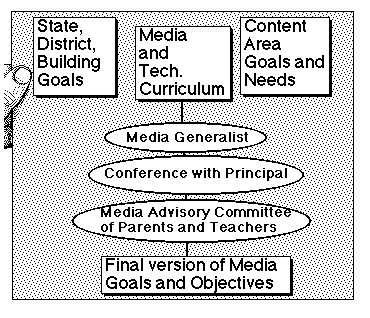

Under each of these categories I write one or more long term goals. I used the description of “goals” from A Planning Guide for Information Power1 to help write these: Goals are broad statements describing a desired condition. As much as possible I relate my media program goals to any state department, district, and building objectives; the media/technology curriculum; and content area department goals. I try to write program goals which, while attainable, will also make me stretch, make me work, make me think creatively. It is better goals be over-ambitious than under-ambitious. These goals reflect where the program should ideally be in five years.

Under each goal, I create one or more yearly objectives, or indicate “no action”. Again I used the planning guide’s definition: Objectives are short-term statements that describe the results of specific actions. Each objective I write can be done. Each objective is realistic. The number of objectives I write, however, is purposely ambitious. I will have to work very hard to accomplish every task, and I realize that it is possible not every objective will be met during the planning year. I believe this “over-planning” is important, and I’ll discuss why later.

Next I solicit approval and advice about this draft version of my goals. I give my principal, curriculum director, and major department heads copies of the document, and schedule a meeting with the principal for a week later. The intervening week gives him a chance to read the goals and objectives and reflect. In our meeting, I try to make sure the principal understands each goal, knows how it affects the entire school program, and recognizes the cost of each goal in money and/or labor. I also suggest that this document can help him write my yearly job evaluation. I use the principal’s comments to make modifications in my long and short term goals.

I also take the draft version of my goals to my hand-selected library/media advisory committee. This committee consists of a mix of school opinion leaders, active media center users, and parents. I again see that each member of the committee has a copy of the goals for a week before our meeting, usually held in the evening at my home. Again, my aim is to clarify the goals and objectives for the committee members and get input from them for modifications and additions to the goals.

If your school is not one which has had an active, vital media program, both the principal and media committee may do little more than “rubber stamp” what you have written for the first year or more. As your program becomes more visible and the principal and committee members more knowledgeable about what you and your program can accomplish, expect more suggestions at your planning sessions.

I regard this planning process as the most important thing I do each year. Not only does it give me a focus for my daily activities, it also gives my media program a broader base of support. It’s not just me who wants the media program to function effectively; a dozen other professionals and parents also have an interest in its success. The principal has changed from an agent of malevolent criticism, apathetic ignorance, or benevolent neglect to a committed supporter of a program of acknowledged value. Budget and staff requests can be directly related to program goals. And should budget or staff cuts threaten the media program, I can at least say, “But look, here are some goals and objectives to which you, faculty members, and parents have agreed. How am I going to meet these objectives without financial and clerical support?” The burden of making the program succeed is shared.

By getting input from other professionals in the school, I am also giving myself a yearly “reality-check”. Areas which I think are important, may not seem as important to the faculty. For example, an inservice on desktop publishing may be of higher priority to teachers than learning about the hyperware which excites me. Teachers might report that students are having difficulty finding good fiction in the collection. Perhaps building the reference collection should be given second priority. Listening to this formal committee’s comments alerts me to problems I may be too near to recognize, and to the special needs of my individual building.

I keep the finalized goal and objective document handy and refer to it at least once a month. It serves to help me prioritize my purchasing and use of discretionary time. I also use it as a guide to the other “end” of the planning/reporting process: reporting. The document helps me decide what to communicate to my administration, faculty, and community.

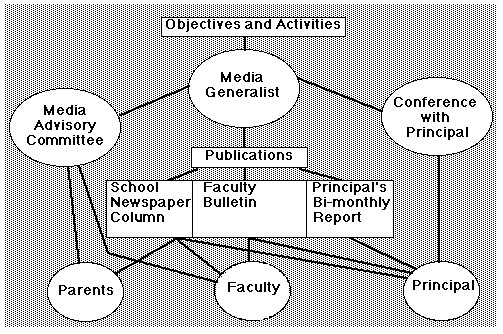

My public relation efforts center around three reporting tools: a bi-monthly principal’s report, a monthly faculty newsletter, and a regular column in the school district’s monthly newspaper. While each of these “publications” has a different audience and different focus, I often address common topics which relate back to my program goals or year’s objectives. While a yearly evaluation with the principal or a yearly report to the advisory committee could suffice, monthly or bi-monthly reports keep media activities visible throughout the year. These writings reach a wider audience: the entire staff and the community, not just the administration and the selected library/media committee.

The bi-monthly principal’s report covers nearly all activities in which I am involved over a two-month period, succinctly described. I mention the teachers whose classes are using the media center and with whom I have been cooperatively teaching; new materials and how they are being used; inservices given; special administrative tasks and problems; circulation and media center usage figures; and professional activities including workshop and conference attendance. My desk blotter calendar and appointment book help remind me of my previous month’s activities. I keep the reports upbeat, complimentary, and as short as possible.

The faculty newsletter contains information which I think teachers will find usable. I highlight new materials and equipment, remind teachers of media services, and briefly describe resource units teachers and I have taught. This newsletter is never more than a double-sided page long incorporating lots of white space, cartoons, and clip-art.

Finally, I write a column for the school district’s monthly newspaper. Single, broad-based topics are covered: the role of computers in schools, the media skills curriculum, interlibrary cooperation, how the media program supports whole language instruction, new technologies, etc. I solicit topic ideas and writing from the other media specialists in the district which can be used in the column. The purpose of the column is to explain, in lay-terms, how the media program benefits the reader’s children: creating life-long learners, making informed decision makers, and providing alternative learning opportunities for at-risk students, the learning disabled, and children who are primarily visual learners. I try to write in a readable, and, when appropriate, humorous manner. I also keep in mind that while I write the column for parents, the majority of the school’s staff and students also read the newspaper. I also report formally at the end of the year to the principal and advisory committee using the planning document to give an honest appraisal of how well the goals and objectives for the year were met, successes and problems. I have never accomplished all my yearly objectives. Remember these are purposely ambitious in number. I believe it is more psychologically beneficial to diligently work to my ability and fall a bit short than to do everything and wonder what more I could have done. It’s also better for the administration and faculty to perceive one as being over-extended than under-utilized. Machiavellian? It works, and to no one’s harm and to my patrons’ benefit.

As professionals, we believe in our efficacy and that our efforts benefit students and staff. We know how hard we work. We know that we cannot create resources to support good programs out of sweat alone. We see on a daily basis the excitement of child who has found a book which speaks to his heart, a computer program which challenges his mind, or a videotape which answers questions he has about his world. We see children not served by textbooks, learning because a teacher uses more than just the textbook. We know the more informed decision makers and life-long learners we create, the better society will become. But for us alone to know this is not enough. We must share what we know and what we do in a systematic way. Then we can build a common cause in our schools and community by building a common information base. That’s information power!.

1. A Planning Guide for Information Power: Guidelines for School Library Media Programs. Chicago: American Library Association, 1988.