Top Ten Secrets for a Successful Workshop

Library Media Connection, October 2006

Congratulations! Because of your recognized expertise in an area - gained through research, study or practice - you have been selected to give a conference workshop! This just is the first step toward celebrity status in the library world. Your own line of designer clothes, a private jet, and fawning fans will soon follow. Start thinking about how to avoid the paparazzi!

Sorry, got carried away.

As a veteran workshop presenter, attendee and high school speech teacher, I’d like to offer 10 suggestions on what makes a superb experience for both the participant and you. Advice is normal text and an example follows in italtics.

1. Know your role.

The focus of a good workshop is building basic understandings, teaching key concepts, and allowing practice of some useful skills. Think of yourself as a workbook, not a textbook. The real genius of most workshops is the ability to take a complex topic and make it understandable and useful rather than to give in-depth “coverage” or to display one’s commanding mastery of a topic. In writing, Stephen Jay Gould has done this with science – making difficult concepts understandable to the layperson. Take a good look at the strategies used by the For Dummies series – lots of lists, lots of analogies, and an emphasis on the practical.

You can and should build participants’ confidence by being approachable and giving them respect – not through overwhelming them with factoids, three-letter acronyms and long, detailed background information. Do not draw attention to small errors that you might make during the workshop – “Gee, I see I made a really stupid spelling error on this slide” or “I guess I forgot to include that in the handouts.” Trust me, nobody notices these sorts of things until you point them out. People really do want presenters who know what they are doing - or at least appear to.

Gee, I’ve really been doing a lot with digital photography both at home and school. I’ve read up on it, I’ve reapplied some of my training in 35mm photography, and some of the things I’ve done with digital photography in school have been effective. I think I’ll do a workshop for the next library/technology conference!

I know not everyone is as into photography as I am, but there are some pretty simple ways everyone can both improve the quality of a digital picture and use it a teacher. I’ll assume people have a fairly inexpensive camera, limited editing software, and lots of other things to do in the classroom than use photographs.

Let’s call the workshop: It’s a Snap! Making the Most of Digital Photography in Your Classroom.

2. Limit your topic.

Although it is counterintuitive, your biggest problem will not be finding enough to talk about, but limiting what you will present. You have a topic – now take time to determine the 3-4 key understandings or skills you want people to leave feeling they have down cold. Remember, your goal is to empower, not overpower.

So then, here are my goals:

- Help participants understand how powerful using visuals are in teaching, especially with this generation of learners.

- Teach some simple techniques for taking and editing digital photos.

- Show some ways a teacher can use digital images in materials created for students and some simple projects students can do with digital cameras.

Your key understandings or skills should be your presentation’s organizational road map, each understanding or skill building on the previous one. While it is important that you know where you are going, it is just as critical your participants know this as well. In your talk, slides and handouts, use this map to help both you and your participants stay focused. As you move from one understanding or skill to the next, take a moment to review the previous understandings.

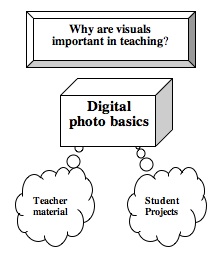

A graphic representation of this map is very helpful for most participants (since there are more visual learners than meet the eye.) This can be as simple as three or four different colored textboxes repeated throughout your slides or as complex as an Inspiration-designed concept map.

The map for my presentation:

4. Set out a problem or possibility then offer a solution or opportunity.

Obviously you think the information and skills you are teaching are important to the participants. Do they know that? Don’t assume so. One masterful way to develop both interest and attention, is to start with a seemingly insolvable problem or terrific opportunity, and then show how your workshop will help folks solve that problem or take advantage of that opportunity.

A short check at the beginning of your talk about the composition of your attendees will help you ingeniously “customize” your workshop on the fly. The examples you use might differ if your group is mostly librarians, mostly technologists, mostly classroom teachers, or mostly administrators – or the level of expertise the group my already have with a technology.

The short check can be as easy as simply asking at the beginning of the talk, “How many of you in here are classroom teachers? Librarians? Etc.? Another good way to get to know your group is by asking an open-ended question about your topic. “What is biggest difficulties your students face in doing good research?” or “Why don’t some students read voluntarily?” or “What problems do you encounter when trying to do digital photography?”

My introduction…..hmmm, let’s see.

- 1. I think I’ll pose the questions, “Do you have students who don’t seem to pay attention? Do you have students that have a hard time understanding concepts through reading? Would you like a quick and easy way to integrate technology in your classroom and give students practice in a new form of communication?

- 2. Then I will ask participants to complete a short checklist on using digital cameras and photos and then ask them to share how they did.

5. Be conversational and have fun.

You do not have to be a powerful orator to be a good workshop presenter. In fact, a formal speaking style will work against you. Instead, envision yourself in your living room visiting with a group of good friends and use the same conversational approach. Build a human connection between you and your group – whether it is five people or 500. Even if you have been given an introduction by a room host, take about three minutes (no longer) to let the participants know you are actually a human being – a brief summary of career, an experience that got you interested in the topic, etc. (Oh, the old advice to picture your audience naked does not work – depending on who is in the front row, you will either be so aroused or grossed out, you won’t be able to concentrate.)

Think about stories you can share that help you make your points clearly and effectively. All great teachers are basically effective storytellers. Not only do the concrete examples create interest and provide experiences to which the participants can relate, stories will build that human connection.

Finally, remember that if you are not having fun, probably nobody else is either.” A good laugh, either intentional or unintentional, that comes as a result of either a comment by you or a participant is a very good thing. Humor helps create that vital affective bond between presenter and participant.

I’ll try to add some fun and humanize myself by:

- Using some family photos as samples to practice editing.

- Making sure I tell about the project Stacie did in my class that included a picture of her mom in her bathrobe and her dad drinking a beer.

- Showing some examples of my own bad photos and how I improved them.

6. Good handouts and good slides that compliment rather than duplicate.

In Secret 1, I suggested that you should consider yourself the workbook, not the textbook. This is not to dismiss the fact that attendees may want detailed, complex materials for further study. Your handouts can provide that information through reprinted articles (with permission), annotated bibliographies, links to websites, or detailed charts and graphs.

When it comes to complex information, Edward Tufte in his short book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information 2nd ed. Graphics Press, 2001) makes a great case for using handouts instead of PowerPoint. The other great use for handouts is as a guide to the activities that will be described in the next section.

My thoughts on good PowerPoint use are summed up in an old column “Slideshow Safety” <http://www.doug-johnson.com/dougwri/slide-show-safety.html> so I won’t repeat them here. Succinctly, there should be a compelling reason for a slide to exist. It needs to contain a short key point, movie, graphic, discussion question, or activity prompt. Slides should not contain the entire text of your presentation so you can simply read them. I’ve see too many presenters do just that and I just want to dope slap ‘em. Less is more.

Do think about this: the visuals on your slides can be highly affective as well as cognitively informative. By association, your believability (and likeability) will increase if you use photographs of happy smiling students or teachers. For that artistic look, run them through a filter in an editing program. (The latest version of PowerPoint allows you to do this within the program itself.) As suggested earlier, a graphic “road map” helps organize your participants.

My handouts will include:

- A bibliography and links to some good sources about choosing a digital camera, visual literacy and learners, a primer on good photo taking, a link to AtomicLearning’s section on photo editing using iPhoto, and a list of popular digital editing software.

- Work areas for the activities I will do including critiquing a photo, cropping a photo, brainstorming ways to use digital photos in my lessons, and creating a project in my curriculum that asks students to use digital photos.

- Examples of a student handout, a lesson supported by photographs I’ve taken, and a letter to parents that used digital photos.

- Lesson plans with assessment tools (primary, middle and high school) that gave been used successfully in my school.

My slides will include:

- My organizational graphic.

- My major points and discussion questions and activities instructions.

- Examples of photographs to critique.

- Examples of photographs before and after editing.

- Examples of student projects that have used student-produced photos.

- I’ll illustrate all slides with photos of my kids working with cameras and editing software.

7. Less talk, more action.

I know without a doubt that I am never bored when I am the one doing the talking. I can’t say the same for the folks in my workshops, so I try to give them every opportunity to do other things than simply listen. I once had a Bureau of Educational Research professional speech coach suggest to me that one never goes for more than 20 minutes without an activity that involves the participants. These “activities” can be as simple as “Share with your neighbor two ways…” or “Jot down one way you might use this idea in your classroom” or “Everyone stand up and repeat after me…” The idea is to get minds out of neutral and into gear and simulate discussion. Other more formal activities (which I always ask be done in small groups) include taking a short quiz, doing a Edward de Bono PMI activity, or filling out a bubble diagram in the handouts. If you if direct questions to the whole group, make the questions both easy and open ended. Questions calling for a “correct” response make you sound like the teacher in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Oh, activities are a great way to control the length of your workshop. If the workshop is running long, don’t give participants much time to it; if the workshop is running short, allow more time.

Computer labs, of course, should be nearly all “group” participation and hands-on. For more about this special kind of workshop see my “Seven Habits of Highly Effective Technology Trainers” (Appendix to the article at: <www.doug-johnson.com/dougwri/why-what-how-and-who-of-staff-development.html.

Oh, and give people a break for goodness sake somewhere after about an hour and fifteen minutes. The mind can only absorb as much as the butt can tolerate, right? Presenters more clever than I have designed activities that get people standing or moving around

Activities:

- The opening quiz.

- I’ll ask “Who is the worst photographer in your family and why?”

- I’ll ask participants (in pairs) to critique a photo and offer advice on how it should be edited.

- I’ll ask participants to brainstorm at least 3 ways they can used digital photos in their own instructional practices and communications.

- I’ll have teams of participants pick a curricular unit and design a project that asks students to use digital photos.

If I have a lab and this is a full-day workshop, I will ask participants to practice cropping, eliminating red-eye, and “enhancing” a photo they have taken.

8. Give a chance to practice, apply and reflect.

The best workshops are ones that not only introduce me to new ideas, but reassure me about my current practices. Send folks away with some “low-hanging fruit” – very simple suggestions for things that they can implement the next day back in school. And finally, allow some time for participants to reflect on their own practices. How often does that happen on the job?

Great workshops are the ones that feel more like a conversation than a lecture. If I, as the workshop leader, don’t learn something from the participants about the topic, I have not been successful. It is amazing what good ideas participants bring with them and getting them to share those ideas with the group is an important part of your job. While I dislike the term facilitator, it happens to be just the right term in this case.

So then, you give people a chance to discuss and what happens? Somebody makes an off topic or hostile comment or asks a question from far left field. Or somebody sets out to show that he (almost always a he) knows just a whole heck of a lot more than you do about this particular topic. The trick is to both ignore and honor those folks and never get rattled, angry or defensive. Practice responses like these:

- That sounds like something that I need to do more thinking about myself.

- That’s a great question and I’m afraid we’d need a whole other workshop to answer it.

- Gee, what does the rest of the group think?

Of course you can always break down in copious weeping, but you will still need to go on with the workshop eventually.

I will remember to use my activities and when critiquing photographs, make sure the participants are the ones offering the suggestions.

I’m guessing my “create a photographic timeline of your Saturday” will be a project everyone will feel s/he can do with students. Most participants will also appreciate the simple tips I’ll give for improving their picture taking.

(I’d better remember to put in the description of the session that the workshop is for beginners!)

9. End with a summary, on an upbeat note, and on time.

At the end, repeat your initial goals for the workshop and quickly summarize the main ideas. As I used to teach my speech kids:

- Tell’m what your going to tell’m.

- Tell’m.

- Then tell’m what you just told’m.

Your last remarks should offer a charge to your group to apply the skills they’ve just learned. A little inspiration or humorous quote brings closure. Say thanks and give participants a way to contact you with follow-up questions. Ask the nice ones to fill out the session evaluation form.

And this might be the most important factor of all, end on time or even a little early. I have yet to hear a single complaint about a workshop that ended at 3:45 instead of 4:00. In fact, a cheap way to be very popular is to make sure you end early enough for your group to be first in the lunch line, at the exhibits, or in the bar. Ending more than 5 minutes late is criminal under any circumstances and may qualify as torture under the rules of the Geneva Convention.

This is easy. Using my graphic, I’ll summarize the major points I talked about:

- Visuals can help students learn and students like communicating visually. Digital photography makes that easy.

- Remember the simple photo taking skills I suggested and some editing techniques.

- We looked at some ways that you as a teacher can use photographs in teaching and communicating.

- Think about where you can give students a chance to use photos they’ve taken to communicate.

I’ll encourage them to start simple and know that every project gets better.

How’s this for an ending quote? “Treat your students as you do your pictures, and place them in their best light.” Paraphrased from Jennie Churchill.

I’ll remind the group that my e-mail address is in my handouts.

10. I’m letting you out early. See above.

Any complaints?