MultiMedia Schools, Jan/Feb 2003

Ever hear these?

- I just can’t get the teachers excited about using technology as a part of their instructional units. They say the stuff never works at the critical time.

- Those technicians! They have the computers so locked up, the kids can’t do anything.

- Seems like we are always short of powerful computers for students, but the folks at the district office always seem to have new machines.

- Another gradebook program to learn! Why can’t the district just pick one and stay with it?

- You are putting my child’s records on-line? How do I know they will be secure?

- We’d like to do more constructivist-based units but it seems the resources just aren’t there.

- What do kids really need to be able to know and do with computers?

Such questions often stem from a lack of having a holistic view of technology use in schools. The magazines teachers read stress the classroom uses of technology. The conferences educators attend often are filled with vendors who are trying to offer instructional management packages or software solutions that are only small pieces of the educational technology use puzzle. Staff development efforts focus on learning how to use management software without helping the teacher understand how their efforts fit into the overall school goals. Why does this occur?

When I came into my job as technology “supervisor” in the Mankato Public Schools in 1991, my department and I focused almost exclusively on the teaching and learning applications for our few Apple IIs in the district. Great fun. These clever software programs excited the kids and gave a few teachers a new reward system or a way to keep kids busy.

But over the past 12 years, our department and district have spent an increasingly higher percentage of our technology dollars on infrastructure, management software, online content, and tools for the teachers themselves. I have concluded that, while not nearly as exciting nor as much fun, it is in the long haul probably wiser. As I tried to understand why this shift has occurred, I began thinking about technology planning and implementation in terms of hierarchical needs. And I have become convinced that everyone effected by the educational uses of technology needs to understand the overall dimensions of its use if they are accept its use. What follows is a planning model that is comprehensive and simple enough for a common understanding by all stakeholders effected.

Maslow and motherboards

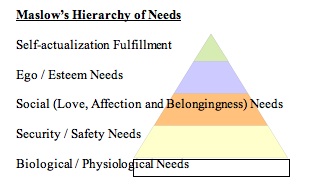

Most of us remember Maslow from our college education foundations classes back in the last century.

In simple terms, Maslow’s theory states that before one can have the important things in life such as love, self-esteem, or fulfillment, some basic needs such as food and safety must be met.

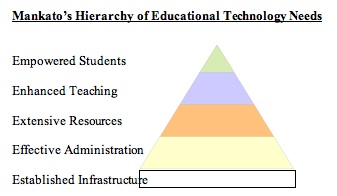

I think we can extend Maslow theory to technology implementation in schools as well. I have called this new theory, Mankato’s Hierarchy of Educational Technology Needs. Much as Maslow theorizes that physiological needs come before psychological needs, I would suggest a school district must meet its infrastructure needs before it can reach its goal of using technology to empower learners. A visual is below:

Below I have described each of the “needs” in the diagram and show how it impacts student performance, and why it, if not met, keeps schools from being able to use technology in ways that have a positive, measurable impact on learning.

Established Infrastructure

The district will have a reliable, adequate, cost-effective, and secure technology infrastructure that supports the learning, teaching, and administrative goals of the district. (See Table One for some indicators of this goal having been met.)

One of the most critical and potentially limiting factors in the successful implementation of information technologies in schools is reliability. Nothing keeps an administrator from using a data mining tool, a librarian from using an online database, a teacher from using a web-based lesson plan, or a student from creating a multi-media presentation like the uncertainty that the technology will fail at a critical moment. We rely on electricity, natural gas, television, and telephone services (as well as 16mm projectors, videotape players, and overhead projectors) because these technologies have reached “5 Nines” reliability. We can count on them working 99.999% of the time. While techno-advocates often ask users to have a back-up plan in case of technology failure, users have been reluctant to take this precaution. Why? It effectively doubles one’s workload.

Adequacy is a second important criterion that must be acquired before users in schools will trust technology for the completion of critical tasks. Administrators will not use online accounting systems if there is a long delay in accessing the program because the network will not support the bandwidth. Teachers and librarians will not plan units that call for the use of electronic sources of information if there are too few computers for students to use. Students who cannot rely on working technologies because technicians are overloaded with work will find other means to complete assignments.

Finally, security keeps many users from trusting and using technologies in school. Good data back-up practices, data privacy policies and their enforcement, and cutting-edge security hardware and software properly configured that prevent unauthorized internal and external access to both personal and organization data on school networks are critical needs for all organizations. Schools are only slowly coming to understand this. A lack of IT professional expertise in many school districts has caused this. Not just educators, but parents are skeptical of the extensive use of digital record-keeping if they cannot be assured that confidential information about their children will remain confidential.

Effective Administration

The district will use technology to improve its administrative effectiveness through efficient business practices, communication, planning and record keeping. (See Table Two for some indicators of this goal having been met.)

Schools are also businesses. They must have good accounting, budgeting and purchasing practices if they are to have credibility with the tax-paying public. They must maintain records of test scores, grades, and attendance of students for state, local, and parental reporting. They must keep personnel records and meet payroll. They must track and control transportation, food service and special education spending. And all of these needs must be met before teachers can teach and students can learn.

Increased demands for accountability by the public of both expenditures and student achievement have also increased the need for more accurate and sophisticated administrative technology uses in schools. Efforts to tie measurable student achievement to specific educational practices and their funding will mean educational decision-makers need to gather, organize, store, extract, and analyze data in powerful ways. Effective, efficient data-mining practices are possible only with information technology and educators trained in its use.

Efforts to give educational consumers (parents) the ability to compare schools have resulted in K-12 schools competing for students. This competition has led to a new emphasis on using technology as a communication tool. The ability to use communication technologies such as email, electronic mailing lists, and websites are playing an increasingly important role in how schools both inform parents and the public and receive feedback from them. Schools need to see information technologies as a marketing tool. Access to real-time data about their children’s daily performance through web-accessible gradebooks and attendance records, teacher webpages, and curriculum outlines and outcomes, as well as comparative student achievement data to other local schools, will be as important for schools to provide as online banking services are now for financial institutions who wish to remain competitive.

It is not just student learning that will suffer as a result of inattention to the administrative uses of technology, but the existence of individual schools themselves may hang in the balance.

Note that both these lower levels (infrastructure and administrative use) of technology planning do not directly involve student use. But they both have an impact on learning. Schools that use technologies to increase administrative efficiencies can spend more money on direct instruction: better resources, lower class sizes, a better trained staff, etc. These uses support any form of instructional practice, from traditional to constructivist.

Extensive Resources

Technology will be used to provide the most current, accurate and extensive information resources possible to all learners in the district and community in a cost effective and reliable manner at maximum convenience to the user. (See Table Three for some indicators of this goal having been met.)

Progressive thinkers in both education and business recognize that basic skill acquisition and a memorized core of facts, while important, are only the foundation of a 21st century education. The ability to work collaboratively, recognize and solve genuine problems, evaluate and use information from both primary and secondary sources, communicate effectively, and assess one’s own performance are the new “basic skills” for workers in an information-based economy.

Unfortunately, many teachers are reluctant to implement a project-based, constructivist approach to learning because of the lack of resources that their students can use. Ironically, budget makers often question why expenditures are necessary when “our” teachers just use textbooks as the primary information source for instruction. This is a genuine Catch-22 situation.

If teachers are to design curriculum, instructional units, student activities, and assessment tools that teach these skills, they will need more extensive information resources than in the past. Both information in print formats (made more accessible through electronic library catalogs and periodical databases) and in digital formats such as online or CD subject area databases, full-text periodical databases and reference tools are necessary if students are to have the learning experiences that lead to the ability to access, process and communicate information. Information processing and communication tools are also necessary: word processing programs, desktop publishing software, spreadsheets, databases, visual organization tools, web creation software, graphic creation tools, and digital still and video editing tools.

Teachers need access to professional resources that will help them improve their own practice as well. Access to professional research such as ERIC databases, electronic journals and mailing lists devoted to professional practice, and online classes and tutorials can be effective components to any staff development effort.

I would include in this category the need for school library media specialists and technology integration specialists who use their expertise to help both teachers and students use these resources meaningfully. Too often human resources are not seen as integral to the successful implementation of technology.

Enhanced Teaching

All district teachers will have the technology training, skills and resources needed to assure students will meet local and state learning objectives and have the technological means to assess and record student progress. (See Table Four for some indicators of this goal having been met.)

The meaningful use of information technologies by teachers falls into two categories: personal productivity and transformational, similar to Shoshana Zuboff’s automating and informating, as described in her classic book In the Age of the Smart Machine (Basic Books, 1989.).

Teachers can design more easily-read worksheets, guides and objective tests - all easily modified using a word processor. They can more quickly report student grades and attendance using a networked administrative system. They can communicate more effectively with students, other staff members and parents if they can use email and create webpages. No educational practices genuinely change with these kinds of uses, but traditional tasks can be done more efficiently. If a teacher spends less time creating instructional materials, recording and reporting student progress, and communicating with parents, the time saved can be used for direct interaction with students or on designing more effective lessons or units.

The transformational use of technology changes the role of the teacher as well as what is taught and how it is taught. The technology is used to actually restructure the educational process to allow it to do things it has never been able to do before. These things include assuring that teachers can:

- Provide instruction that insures all students master the basic skills of writing, reading, and computation.

- Design and implement constructivist-based units that provide students instruction and practice in authentic information literacy and research skills and the higher-order thinking skills inherent in them.

- Design student performance assessments that lead to improved learning.

- Use assistive and adaptive technologies with special needs students.

- Provide students and parents with

- individual education plans (IEPs).

- continuous feedback on how well students are meeting their learning goals.

- opportunities for virtual student performance assessments.

- Locate and use research findings that will guide their educational practices.

- Collect and interpret data that measure the effectiveness of educational practices.

Society is asking schools to do two simple things: guarantee that every student has basic skills and prepare an ever larger number of graduates for an information-based (or knowledge-based) economy that requires workers who are self-motivated, can solve genuine problems, communicate well, have the interpersonal skills to work collaboratively, and can upgrade their skills by purposely continuing to learn. Teachers who are well trained in technology may be the only thing schools will have to achieve these results.

Again note that this lower level of technology planning does not directly involve the student use of technology. But it has a considerable impact on learning. Teachers who use technologies can improve traditional methods of instruction. Constructivist, problem-based units can certainly be designed that do not need technology, but such units can be greatly enhanced by its use.

Empowered Learners

All students will demonstrate the mastered use of technology to access, process, organize, communicate and evaluate information in order to answer questions and solve problems. (See Table Five for some indicators of this goal having been met.)

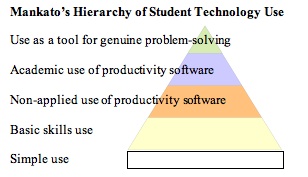

When the basic needs of infrastructure, administration, resources, and teacher understanding are met, schools can provide students successful technology-enhanced learning opportunities. Student use of technology can be viewed in a hierarchical arrangement as well:

Simple use

Drill and practice software, integrated learning systems, computer-animated picture books, trivia recall games, low level problem-solving and simulation computer software have long been the mainstays of technology use by students in most schools. This is also where a good deal of effort has gone in assessing the effectiveness of “educational computing” with poor, or at least mixed results. The use of technology to teach basic skills, memorized facts, or low-level thinking skills, while at times motivational for very young or at-risk students, is very expensive for the results achieved. (My cynical side says this use of educational computing is attractive to administrators who hope that well-designed programmed instruction can overcome the disastrous performance of students with poorly trained or incompetent teachers.) The assessment of this use of technology really has to be an assessment of total student gain of rather low-level thinking skills, and is extremely difficult to determine for many reasons - Hawthorne effect, bias of software producers who may be conducting the evaluations, lack of resources for controlled study groups, etc.. Unfortunately, this technology use seems to be currently tainting the attitudes of decision-makers about all uses of technology in schools. And the actual computer skills needed by students to use these products is very limited: using a mouse to point and click.

Basic skills use

The second level of technology use is operational. Knowing how to turn on a computer or other piece of equipment, to save files, to print, to adjust desktop settings, and to add or remove software are necessary for most independent computer users. In a school setting, however, many of these activities are restricted or at least discouraged. Management tools are designed to direct students directly to the applications they need without the distraction and possible damage altering systems operations entail.

Non-applied use of productivity software

Pull-out classes in “computer literacy” teach students at all grade levels productivity software such as word processors, databases, spreadsheets, presentation programs, multimedia authoring tools, e-mail, video production equipment, digital reference materials, electronic indexes, and network search engines. While all students should acquire these skills, if they are not applied to a purpose, the skills are somewhat meaningless and soon forgotten.

Academic use of productivity software

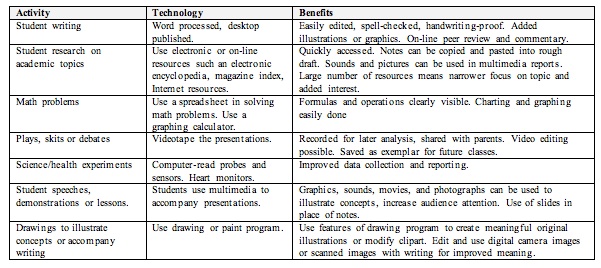

Increasingly teachers are giving traditional assignments a “technology upgrade.” Traditional tasks are completed using technology and technology adds benefits to those tasks. For example:

While upgrading traditional assignments with the judicious use of technology helps students apply computer skills and improves traditional instructional practices, it still does not tap into technology’s potential to serve as a catalyst for pedagogical change, nor does such a scattershot approach guarantee that all students, regardless of teacher or program, will gain identified technology competencies.

Use as a tool for genuine problem-solving

When students use technology as a tool for completing complex, authentic projects that ask them to solve genuine problems and answer real questions, technology reaches its most powerful instructional potential. This use asks students to complete tasks similar to those they will be asked to do in information-economy jobs - the kind of work that is both better paying and gives greater job satisfaction.

But big challenges present themselves when technology is used on a large scale as an information-processing tool. First it requires a good deal more investment in time and effort on the part of teachers in learning how to use it. Anybody can learn to operate drill and practice software in a few minutes, but learning to use a database to store, categorize and sort information can literally take hours of instruction, weeks of practices, genuine effort and guaranteed episodes of pure frustration. Teachers must spend additional time developing lessons that don’t simply incorporate the computer productivity skill into their specific subject areas, but developing units that have meaning for students, stress real-world applicability, and require higher level thinking skills.

Second, the product of such instruction is not a neatly quantifiable score on an objective, nationally-normed, quickly scored test. Conducting and assessing such projects require the ability to develop and apply standards, delay for long periods of time the satisfaction of task completion, and acknowledgement and acceptance that conclusions, evaluations and meanings which result from the efforts are often ambiguous. It means teachers seeing evaluation as a growth process, not a sorting process.

And finally, students need more than the 20-40 minutes of lab access time per week to learn these uses of technology. That means more equipment and software, and making the technology available in more locations (including classrooms and media centers) than if computers are used simply as electronic worksheets of flashcards.

Assessment of this technology use needs to be done less to satisfy a state department, legislature, or academic body, than to inform the students themselves, their parents, and the community in which they live. It means school district curriculum departments undertaking the difficult task of creating benchmarks that describe student information and technology skills at various grade levels and designing the assessment tools needed to measure progress toward those benchmarks. It means finding ways to aggregate the assessed benchmark data to determine how well the entire program or school is doing. It means using technology to build personal portfolios of thoughtful, creative work which students and teachers can share with parents; to present worthwhile and authoritative reports to classmates; and to make meaningful efforts aimed at solving genuine personal, school or community problems. It means adopting an approach to “technology literacy” for all students that is as serious as is the teaching of reading, writing and mathematics. It means being able to determine if the use of technology is making our children better citizens, better consumers, better communicators, better thinkers - better people.

Implications for technology planning and acquisition

While the hierarchical nature of effective technology implementation needs to be understood, that does not mean each level needs to be complete prior to working on the next level of use. In reality, no goal will ever be completely met since technology is in a constant state of change.

Infrastructure needs will grow in capacity, stability, and security. Administrative uses of technology will expand, especially in the areas of data-mining and communications. New online resources of value to staff and students are continuing to be developed. Staff skills will continue to change as curriculum, software and hardware change. And students will be expected to grow in sophistication, not just in the use of technology, but in problem-solving and creative thinking.

For each major area, our district writes annual objectives. The following tables provide a simple planning tool we use in helping set those objectives. We relate each technology goal to its related educational objective, evaluate the progress we have made on it, judge its importance to it, and then give it a priority rating that is used when allocating resources toward its completion. This work is done by an advisory committee of representatives from a wide-range of stakeholder groups that meet on a regular basis.

A district plan that addresses each level of a technology hierarchy that is planned and shared with all school staff and the community can help answer and reduce the kinds of questions like those that began this article. It can lead to better budgeting, more effective staff development planning, and an understanding of all the roles technology can play in helping make our schools more effective.

Staff survey for 2004 long range tech planning purposes

Doug Johnson, Mankato (MN) Area Public Schools

Estimated time to complete: 15-20 minutes

The purpose of this survey is to help the District Media/Technology Committee determine how effective the district has been in meeting past technology goals and to determine the areas that should be priorities for technology planning and budgeting for the next three years. Results of this survey will be published on the district website.

The goals for the district media and technology department have been broken into 5 basic areas, and the survey reflects those areas.

- Established Infrastructure The district will have a reliable, adequate, cost-effective, and secure technology infrastructure that supports the learning, teaching, and administrative goals of the district.

- Effective Administration The district will use technology to improve its administrative effectiveness through efficient business practices, communication, planning and record keeping.

- Extensive Resources Technology will be used to provide the most current, accurate and extensive information resources possible to all learners in the district and community in a cost effective and reliable manner at maximum convenience to the user.

- Enhanced Teaching All district teachers will have the technology training, skills and resources needed to assure students will meet local and state learning objectives and have the technological means to assess and record student progress.

- Empowered Learners All students will demonstrate the mastered use of technology to access, process, organize, communicate and evaluate information in order to answer questions and solve problems.

Thanks,

Doug Johnson

Director of Media and Technology

Mankato Area Public Schools

Link here for pdf of survey

April 2008 - Note: I have turned of comments on this post since it has become a spam target for reason. If you wish to comment, email me directly at doug0077 (a) gmail.com. Sorry for the inconvenience.