Creative Commons and why it should be more commonly understood

Library Media Connection, May/June 2009

You’ve heard yourself countless times tell students, “Assume everything on the Internet is copyrighted!”

Sorry. That’s not exactly good advice anymore. Authors, videographers, musicians, photographers, well, almost anyone who creates materials and makes them publically available, has an alternative to standard copyright licensing: Creative Commons. As library media specialists, we need to understand this relatively recent invention and its implication for our staff and students.

Why Creative Commons?

The Creative Commons website explains its mission as:

Creative Commons provides free tools that let authors, scientists, artists, and educators easily mark their creative work with the freedoms they want it to carry. You can use CC to change your copyright terms from “All Rights Reserved” to “Some Rights Reserved.”

In other words, Creative Commons (CC) is a tool that helps the creator display a licensing mark. The creator can assign a variety of rights for others to use his work – rights that are usually more permissive than copyright, but more restrictive than placing material in the public domain. CC makes sharing, re-using, re-mixing and building on the creative works of others understandable and legal. While it has always been possible for a creator to grant rights for others to use his/her materials less restrictively than standard copyright’s “All Rights Reserved,” CC standardizes the process.

Inspired by the Free Software Foundation’s GNU General Public License, the non-profit Creative Commons organization was founded in 2001 by Stanford Law professor Lawrence Lessig. As a part of the “copyleft” movement, Lessig and others believe traditional copyright restrictions inhibit cultural and economic growth. A growing number of content producers want to allow others to use and remix their materials – and in turn be able to use and remix the content of others. CC licenses make this legal.

While Creative Commons was started in the United States, about 50 other countries (as of late 2008) have ported CC licenses to work with their copyright laws. More countries continue to be added. The “International” tab on the CC homepage lists the cooperating jurisdictions.

Understanding Creative Commons Licenses

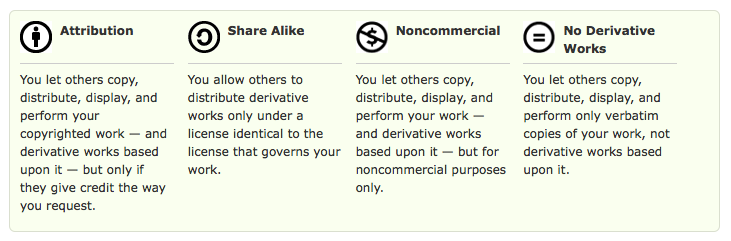

While initially it looks complex, a basic understanding of the types of licenses and how they can be combined is relatively simple. There are only four “conditions” of a CC licenses:

Screen shot from < http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses>

Screen shot from < http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses>

These four conditions can be combined to form six different licenses that specifically describe the conditions creators wish to apply to their works. These are, from least to most restrictive, as described on the CC website < http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses>:

Attribution Share Alike

This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work even for commercial reasons, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. This license is often compared to open source software licenses. All new works based on yours will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use.

Attribution No Derivatives

This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to you.

Attribution Non-Commercial

This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms.

Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. Others can download and redistribute your work just like the by-nc-nd license, but they can also translate, make remixes, and produce new stories based on your work. All new work based on yours will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also be non-commercial in nature.

Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives

This license is the most restrictive of our six main licenses, allowing redistribution. This license is often called the “free advertising” license because it allows others to download your works and share them with others as long as they mention you and link back to you, but they can’t change them in any way or use them commercially.

Two terms that may not completely familiar are “remix” and “share-alike.” Remix, which began as a recombination of audio tracks to create a new song, has become more generic and now implies using parts of many works (photographs, sounds, videos and text) to create a new product. “Share-alike” means that others may use one’s work on the condition that any work derived from the original carries the same licensing permissions as the original. In other words, if you borrow you must also commit to share.

How to use CC for one’s own work

Determining which license one wishes to use has been made simple by Creative Commons. By answering just two questions at http://creativecommons.org/license

Allow commercial uses of your work?

Allow modifications of your work?

the appropriate license will be generated for one’s work, either as embeddable HTML code for a webpage or as text that looks like this:

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA.

That’s it!

Implications for K-12 education

Consider these scenarios:

- A student needs photographs and music for a history project but can’t find what he needs in the public domain or in royalty-free collections.

- A teacher has developed outstanding materials that teach irregular Spanish verbs. She has posted them on a website and now regularly gets e-mails requesting permission to use the materials.

- The media specialist is frustrated trying to help his junior high students understand the rights that intellectual property creators have over their own materials. The kids just aren’t able to see the issue from the creator’s point of view.

In each of the scenarios above, Creative Commons licensing may offer a solution. There are three primary uses:

1. Students and teachers need to be able to find and interpret CC licensed materials for use into their own works. Common advice given to both students working on projects and to teachers creating education materials is to abide by the fair use guidelines of copyrighted materials, search for materials in the public domain, and to use royalty-free work in order to remain both legal and ethical information users. But now understanding and finding CC licensed work is another source of legal materials that students and teachers can use in their own creations.

There are three main ways to find Creative Commons licensed materials. CC has a specialized search tool at <http://search.creativecommons.org>. There is a list of directories by format at <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/Content_Curators>. Google Advanced Search also allows searching by “usage rights.” All can be effective.

2. Teachers should assign a Creative Commons license to materials that they are willing to share with other educators. As K-12 teachers produce and make available course materials on the web, they will need to understand how to give rights to others to use their work. (Check with your local school district to see who owns the copyright to materials that are teacher produced.) MIT’s OpenCourseWare and Rice University Connexions, two formal post-secondary learning materials repositories, are good models of using Creative Commons licensing.

3. Students should be required to place a Creative Commons license on their own work to increase their understanding of intellectual property issues. Only when students begin think about copyright and other intellectual property guidelines from the point of view of the producer as well as the consumer can they form mature attitudes and act in responsible ways when questions about these issues arise. As an increasing number of students become “content creators” themselves, this should be an easier concept to help them grasp:

The Pew Internet & American Life Project has found that 64% of online teens ages 12-17 have participated in one or more among a wide range of content-creating activities on the internet, up from 57% of online teens in a similar survey at the end of 2004. (Teen Content Creators, 2007)

Students need to know what their rights as creators and IP owners are. This may help combat the misperception that only big, faceless companies are impacted by intellectual property theft, and that it is acceptable to steal from big companies but not from the small fry. Too often students and adults forget that many large companies are made up of small stockholders and employees. Publishing companies also represent the interests of individual artists, writers and musicians - whose ranks students themselves may one day join.

Developing empathy toward content creators, who hope to profit by their work, helps everyone place copyright into context and perspective.

In recent years, the legal aspects of intellectual property sharing have been out-paced by the mechanical means of copying, distribution and access. Understanding and using Creative Commons both as content consumers and content producers will help narrow the technology/acceptable use gap.

Spread the word.

Resources:

- Creative Commons website < http://creativecommons.org/>

- Creative Commons wiki <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/>

- “7 Things You Should Know about Creative Commons” EDUCAUSE <http://connect.educause.edu/Library/ELI/7ThingsYouShouldKnowAbout/39400>

Videos

- A Shared Culture <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1DKm96Ftfko>

- Wanna Work Together? < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P3rksT1q4eg>